Enjoy reading? Consider buying the framework as an e-book on Gumroad:

https://sonatasecrets.gumroad.com/l/howmusicworks

4. Four Levels:

The Stairs of Emergence

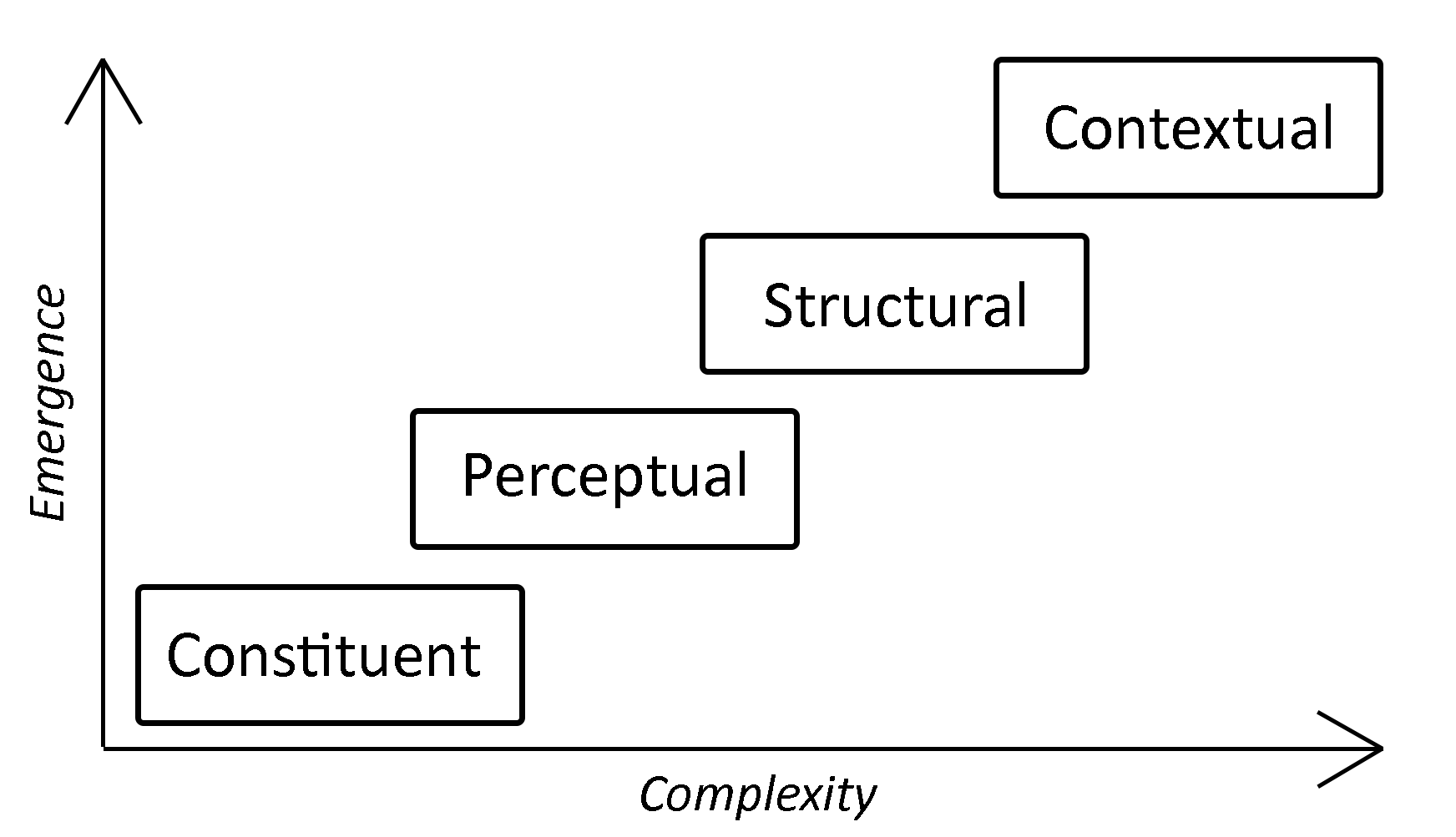

To make sense of the complex stream of sound vibrations and how they are received in our perception facilities, I propose here that it makes sense to divide music into four levels of increasing complexity. Fundamentally, all musical sounds can be reduced to the constituent, basic elements of vibration Frequency (Pitch) and Amplitude (Dynamic) in Time. But there are more musical properties that cannot be possessed by these basic elements alone. They are so-called Emergent properties that arise when the basic elements are aggregated onto a higher level. This is an essential phenomenon of the physical world, for example individual atoms have one set of properties but when they form a molecule that molecule has a new set of emergent properties that was not possessed by any of the individual atoms. (see Oliveira et al 2003).

These basic elements make up what I call the first, Constituent level of music. But when we listen to music, we don’t register a series of consecutive pitches as individual points of data, but always as cohering together in the form of notes in rhythms. This is the second, Perceptual level, which is emergent from the first. We can still “zoom in,” as it were, and identify the elements on the constituent level, but we are predisposed to perceive objects on the perceptual level. Beyond this level we also appreciate how music is put together in larger blocks rather than individual motifs and rhythms. These blocks relate to each other on the third, Structural level, which is emergent from the second, and ranges from the repetition of a short motif to the large-scale form of a whole piece. Finally, when all different music is aggregated as sets of data, the fourth, Contextual level, emerges and concerns relations between different music to each other (Musical-contextual), as well as to other domains in the world (Extra-musical-contextual).

Figure 1: The Stairs of Emergence

We will go through each of these levels in depth in the following chapters, which constitutes the main bulk of the framework. The Constituent level is defined in chapter 5; the Perceptual level is presented in chapter 6 but also requires chapters 7-9 to cover implications of its emergent properties; the Structural level is developed in chapters 10 and 11; and the two types of Contextual level in chapters 12 and 13. Finally chapter 14 grapples with the epistemology of the project and chapter 15 offers some concluding remarks returning to the meaning of music. The remainder of this chapter continues with a further investigation of the initial division of levels.

The Perceptual Sweet Spot

Why is it that we naturally feel consecutive pitches as belonging together in a melody? It’s like when we read – we see the words and perceive their meaning instead of individual letters (then we can “zoom in” to see the spelling with the actual letters). Or if we enter a room with furniture, what do we perceive? We see a table and a chair because they are objects on the perceptual level in space. If we approach them and look closer, we will see that they are made out of smaller parts like legs, planks and screws, but that is not what we see when we first enter the room. It’s the same in the auditory space of music. The legs and screws are the individual pitches, but the actual piece of furniture is some form of musical unit.

This has to do with our ability to keep information in the short-term or working memory as part of our mental faculties. It is needed for our ability to communicate with each other – we need to remember the first half of a sentence in order to understand the meaning of the second half. This takes a few moments, seconds, and we have no problem remembering every single word of the sentence during that time. But after the sentence is finished and a new one is started, the first sentence is dropped from the working memory and the meaning is saved in a longer-term memory. We can no longer remember exactly which words were spoken, but we remember the idea that it communicated. This is only a rough description of the different types of memories and how they work, but it is enough for our consideration of music perceptions here.

The mechanism is the same for music, and I propose that this is how the size of a Musical unit is determined as it is perceived. There is a window, a sweet spot, for our human-calibrated perception in which musical elements cohere and form units. Our short-term or working memory has a clear upper limit to it, so anything that presents a contrast to the previously perceived elements that is greater than a resemblance to them, will be the start of another unit. After a few seconds, when the short-term memory cannot hold more information, the perceived elements are grouped into a unit at a juncture that seems suitable. Notes that lie close to each other in pitch and time are easily grouped together in a melody or a phrase as one type of unit. Notes that come in a rhythmic pattern that repeats in a short time, as an accompaniment figure or vamp, are easily grouped as another type of unit.

This process of hearing music and its relation to our understanding of music (whatever that means) is notoriously difficult to describe and define, because our rational, semantic way of thinking and writing is not really compatible with the multi-layered, interconnected process of music perception in our minds. There are other accounts of this process that uses different terminology but I believe fundamentally share the same underlying ideas: Roger Scruton’s discussion of “grouping” musical elements together when hearing them (Scruton 1997: 309; Scruton 2011: 26-29), as well as Jerrold Levinson’s theory of “concatenationism” of the moment-to-moment sense of listening to music (Levinson 1997; Huovinen 2011: 126-27) (though disregarding his anti-architectonicism).

The theory of perception of musical units described above needs to be amended in two ways to account for music’s high complexity. Firstly, units occur simultaneously as different instruments play separate parts, and create separate units all starting and ending at different times. Some instruments can cooperate to produce groups of elements that are perceived as one unit (for example harmonizing voices to a melody), and one instrument can produce several independent voices as separate units simultaneously (for example piano). The totality of these units occurring in accordance with an intrinsic musical logic is what we call musical Texture.

The second is our perception of units that are starting and stopping at different, continuous times within the texture. Much of the enjoyment of listening to music and being part of “the ride” that music takes us on, comes from when this constant development meets our ears, and our mind latches on to whatever unit presents itself clearest at the time and then moves on to the next. In total, all musical information is too much to handle in real time because the only way the information passes on to our mind is through the short-term memory. The memory needs to package the elements into units for us to make sense of, but the flow of information is always greater than the capacity as long as the music keeps playing. The result is that we let the music envelop us on all sides while we focus on whatever facet we choose as our main focus. We can consciously choose and switch this focus, and analysis tools will help us do so with ease and clarity (see more in chapter 14). If we are really lucky, we can reach a state where it feels like we are actually able to process everything, and it makes perfect sense – the state of absolute Flow. It is truly a remarkable feeling, and one is lucky to experience it even on rare occasions.

Structural Boundaries

Just as human communication uses multiple sentences that follow and refer to each other, so does music with a continual stream of units. Here we reach the structural level, and it basically starts where our short-term memory ends. Or rather it’s the level where we combine all separate “nows,” the musical moments of the perceptual level, into an abstract object that we can see only in retrospect. This aspect is just as vital as the immediacy of the moment but requires very different techniques and approaches to understand and explore as part of music appreciation. In the end, neither one nor the other alone is sufficient for a complete experience, but only together do they provide that kind of deeply meaningful experience music can give us (more on this in chapter 15). But let’s look a little bit closer at the structure side here.

There are many different degrees and types of structure. The first degree is how each musical unit relates to the surrounding ones. In a melody, several notes make up a phrase as one unit, and similarly the structure of a melodic section is the way it is made up of several phrases. In an accompaniment texture, the way accompaniment units are repeated, varied or stopped is its structure of the first degree. In a musical terminology we talk about complimentary pairs like antecedent-consequent, question-answer, call-response or statement-commentary. The way musical units are placed in relation to each other is an integral part of Tonality, the over-arching structural paradigm of all Western music. Tonality gives us harmony as “vertical” musical entities complementing “horizontal” melodic lines, and in chapter 5 we will see how it works in depth and trace its origins from the musical material.

A core mechanism of musical structure is us perceiving Boundaries between consecutive parts and sections. A boundary appears between something that has been and something new. If it’s not new enough, we still perceive it as belonging to what is going on. Only when there has been a sufficient closing or transitional part in the music can we understand it as a new part. But again, this is done concurrently on many different levels, contributing to an ever-increasing complexity. Take a simple case of two phrases that constitute two units, the second answering the first, but then a third phrase follows as a response to both previous phrases. Then the phrase in the middle acts both as an answer on one structural level and half of a statement on another! It’s not practical to develop a generic terminology for specific levels in the structure from here on upwards, because there are so many possibilities of different routes to follow. Instead we have separate terminologies regarding different musical genres and styles, which corresponds to their respective conventions (like exposition and development in classical music, chorus and bridge in pop songs). However, most styles have clear boundaries when a piece starts and ends, framed by silence. On the highest level we talk about the large-scale structure of a piece, and I will use Form to mean this (structure and form can otherwise be used quite interchangeably).

So, a piece is made up of one or more Sections that refers to longer stretches of time comprising units on the first Structural level. And the way a section consists of units is the same way a unit consists of constituent elements: they cohere together stronger than to other units before or after. The whole formation has a fascinating fractural quality in this regard, but the crucial difference is that we cannot use our short-term memory to differentiate between sections, because they go on for longer times. This means that we need to apply a more extensive cognitive process, and it makes this type of music perception more analytical (which we will look into in chapter 14). But some of the structural properties probably work subconsciously as well in recognizing or just sensing a familiarity with longer structural units when they repeat, vary, oppose and return.

There are musical works that consists of several movements – for example sonatas, symphonies, sets and cycles – and they can relate to each other in a Multi-movement level structure or form while each movement has its own form as well. In the analogy with units as furniture, a room with several units of furniture is a section, and a house is a piece with several room-sections in it. A multi-movement work is then a street of several houses, with each house as a separate piece. They have different construction plans and furniture but share the same background view outside the windows.

Context: It's All Relative

The Contextual level comes in two forms. The Musical-contextual level considers only the musical context to a certain piece. There are different genres, styles, traditions and conventions, and music can implicitly or explicitly refer to other music by means of imitation, homage and parody. On the implicit side we find the important aspects of keeping with tradition and breaking it through innovation (which often is a hallmark of music we consider great). This level cuts across both the perceptual and structural levels, and can also be illustrated like this:

Figure 2: The Stairs of Emergence, alternative illustration

The second type is about all aspects that lie outside the actual music, the Extra-musical context. We have already gone through most of them in chapter 2, and in chapters 13 and 15 we will add them again to the equation. First, we consider programs tightly connected to the music like titles and epigraphs, then move on to surrounding circumstances of composers’ lives and times, and finally the context of the situation where the music is played. Hand in hand with both forms of context goes the listeners awareness and knowledge about them, and in chapter 14 we will dive deep into the formation of that knowledge through learning, exposure and analysis.

Previous chapter

3. Identifying Music’s Intrinsic Properties

Next chapter

5. The Constituent Level

Back to Contents